Atomic Theory

Learning Objectives

- State the modern atomic theory.

- Learn how atoms are constructed.

The smallest piece of an element that maintains the identity of that element is called an . Individual atoms are extremely small. It would take about fifty million atoms in a row to make a line that is 1 cm long. The period at the end of a printed sentence has several million atoms in it. Atoms are so small that it is difficult to believe that all matter is made from atoms—but it is.

The concept that atoms play a fundamental role in chemistry is formalized by the modern , first stated by John Dalton, an English scientist, in 1808. It consists of three parts:

- All matter is composed of atoms.

- Atoms of the same element are the same; atoms of different elements are different.

- Atoms combine in whole-number ratios to form compounds.

These concepts form the basis of chemistry.

Although the word atom comes from a Greek word that means “indivisible,” we understand now that atoms themselves are composed of smaller parts called subatomic particles. The first part to be discovered was the , a tiny subatomic particle with a negative charge. It is often represented as e−, with the right superscript showing the negative charge. Later, two larger particles were discovered. The is a more massive (but still tiny) subatomic particle with a positive charge, represented as p+. The is a subatomic particle with about the same mass as a proton but no charge. It is represented as either n or n0. We now know that all atoms of all elements are composed of electrons, protons, and (with one exception) neutrons. Table 3.7 “Properties of the Three Subatomic Particles” summarizes the properties of these three subatomic particles.

| Name | Symbol | Mass (approx. in kg) | Charge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton | p+ | 1.6 × 10−27 | 1+ |

| Neutron | n, n0 | 1.6 × 10−27 | none |

| Electron | e− | 9.1 × 10−31 | 1− |

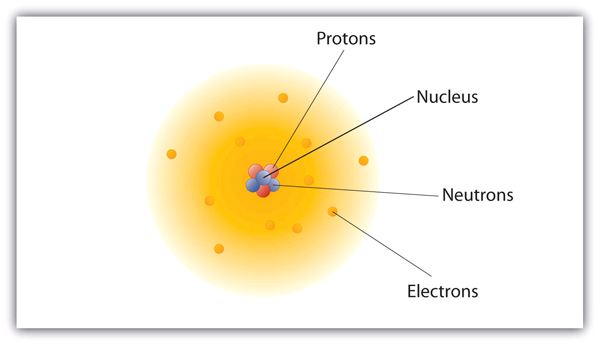

How are these particles arranged in atoms? They are not arranged at random. Experiments by Ernest Rutherford in England in the 1910s pointed to a of the atom. The relatively massive protons and neutrons are collected in the centre of an atom, in a region called the of the atom (plural nuclei). The electrons are outside the nucleus and spend their time orbiting in space about the nucleus. (See Figure 3.4 “The Structure of the Atom”.)

The modern atomic theory states that atoms of one element are the same, while atoms of different elements are different. What makes atoms of different elements different? The fundamental characteristic that all atoms of the same element share is the number of protons. All atoms of hydrogen have one and only one proton in the nucleus; all atoms of iron have 26 protons in the nucleus. This number of protons is so important to the identity of an atom that it is called the of the element. Thus, hydrogen has an atomic number of 1, while iron has an atomic number of 26. Each element has its own characteristic atomic number.

Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons, however. Atoms of the same element (i.e., atoms with the same number of protons) with different numbers of neutrons are called . Most naturally occurring elements exist as isotopes. For example, most hydrogen atoms have a single proton in their nucleus. However, a small number (about one in a million) of hydrogen atoms have a proton and a neutron in their nuclei. This particular isotope of hydrogen is called deuterium. A very rare form of hydrogen has one proton and two neutrons in the nucleus; this isotope of hydrogen is called tritium. The sum of the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus is called the of the isotope.

Neutral atoms have the same number of electrons as they have protons, so their overall charge is zero. However, as we shall see later, this will not always be the case.

Example 3.9

Problems

- The most common carbon atoms have six protons and six neutrons in their nuclei. What are the atomic number and the mass number of these carbon atoms?

- An isotope of uranium has an atomic number of 92 and a mass number of 235. What are the number of protons and neutrons in the nucleus of this atom?

Solutions

- If a carbon atom has six protons in its nucleus, its atomic number is 6. If it also has six neutrons in the nucleus, then the mass number is 6 + 6, or 12.

- If the atomic number of uranium is 92, then that is the number of protons in the nucleus. Because the mass number is 235, then the number of neutrons in the nucleus is 235 − 92, or 143.

Test Yourself

The number of protons in the nucleus of a tin atom is 50, while the number of neutrons in the nucleus is 68. What are the atomic number and the mass number of this isotope?

Answer

Atomic number = 50, mass number = 118

When referring to an atom, we simply use the element’s name: the term sodium refers to the element as well as an atom of sodium. But it can be unwieldy to use the name of elements all the time. Instead, chemistry defines a symbol for each element. The is a one- or two-letter abbreviation of the name of the element. By convention, the first letter of an element’s symbol is always capitalized, while the second letter (if present) is lowercase. Thus, the symbol for hydrogen is H, the symbol for sodium is Na, and the symbol for nickel is Ni. Most symbols come from the English name of the element, although some symbols come from an element’s Latin name. (The symbol for sodium, Na, comes from its Latin name, natrium.) Table 3.8 “Names and Symbols of Common Elements” lists some common elements and their symbols. You should memorize the symbols in Table 3.8 “Names and Symbols of Common Elements”, as this is how we will be representing elements throughout chemistry.